If you’re in Yerevan, you should visit Tsitsinakaberd, as a painful reminder that humanity’s brutality towards one another has no limits. The same applies to memorials to other atrocities.

Tsitsinakaberd, and the adjoining Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute is the main memorial to the Armenian genocide, located in Yerevan, the capital of the modern Republic of Armenia, and the centre of Armenian society. The memorial was built in 1967, following the 1965 Armenian demonstration which demanded that Soviet authorities recognized the genocide, and every year, especially on 24th April thousands of Armenians walk to the monument to pay respects to the victims of the genocide. The memorial is located on a hill to the west of Yerevan, overlooking the city and can be seen from across the city. The location was a relatively short walk from my homestay near Barekamutyun, I just had to walk along Kievyan Street, over the Hrazdan River, then cross the road to climb the hill to the memorial.

An avenue of trees (Figure 1) leads to the memorial, and these have been planted by notable visitors to the site. It is a standard part of a state visit to Armenia that visiting government officials will visit the memorial, the museum, and plant a tree. There are many trees planted by notable government officials from around the world who have visited the memorial.

Once at the memorial, I was greeted by the moving and awe inspiring sight of the monument (Figure 2). The memorial consists of a 44 metre high stele which dominates the skyline and can be seen from all over Yerevan. This stele represents the rebirth of the Armenian nation. Next to it are 12 stones slabs placed in a circle which represent the 12 lost Armenian provinces that are in modern day Turkey and have had their Armenian history as well as populations exterminated during and since the genocide. There is also a wall, with the names of Armenian settlements where deportations took place, and plaques to recognize persons who assisted Armenians during the genocide.

Inside the 12 stone slabs, there are steps descending into a depression. It is here where the eternal flame burns (Figure 3). This flame represents the eternal memory of the victims of the genocide. It is common, especially on Armenian genocide memorial day (24th April) to leave bouquets of flowers here, and they were present when I visited, as were wreaths which were placed around the outside of the stone slabs.

There is a statue at the site of Tsitsinakaberd called Mother Arising Out of the Ashes (Figure 4). This is a memorial to those who survived the Armenian genocide, and thus the name, Mother Rising Out of the Ashes, as the survivors allowed the rebirth of the Armenian nation following the genocide.

At the Tsitsinakaberd site is the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute. This museum is structured in a way that visitors walk through the history of the Armenian genocide according to the well established stages of genocide, which at the time of my visit was the 8 stages of genocide, but has since expanded to 10 stages. These stages being: Identification, Classification, Symbolization, Dehumanization, Organization, Polarization, Preparation, Extermination and finally Denial. All genocides broadly follow this pattern, and we are doomed to repeat history if we do not recognize these steps at the earliest stages and stop future genocides. The history of the Armenians under Ottoman rule provides the background for the genocide, the Ottoman Empire was an Islamic, Turkic Empire in South West Asia, North Africa and South East Europe that arose in the 14th century and ended in the early 20th century. Armenians were an ethnic and religious minority in this empire. As a result of their minority status, they were discriminated against by wider Ottoman authorities. Nevertheless many Armenians were able to attain professional success in the Ottoman Empire, despite the discrimination they faced.

Animosity towards the Armenian minority from wider Ottoman society increased as the Ottoman Empire declined. Armenians came to be regarded as a fifth column, aligning with the empire’s rivals in Christian Europe. Violence against Armenians increased, especially in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most notably in the Adana Massacre of 1909.

In 1915, the Ottoman Empire entered the First World War on the side of the Central Powers. This brought the Ottoman Empire into direct conflict with the Armenian’s coreligionists in Russia. This, and resistance by the Armenians to their persecution, was used as a evidence that widespread rebellion against the Ottoman Empire was taking place in the Armenian provinces, and this in term justified the beginning of the extermination phase of the Armenian genocide.

On 24th April 1915, Ottoman authorities arrested 250 Armenian community leaders in Constantinople. These community leaders were in the main later murdered or imprisoned, in what came to be a decapitation strike that left the Armenian community leaderless and began the extermination phase of the genocide. During this, the Armenian population of towns and villages across the Ottoman Empire was “evacuated” by marching the people by force in the Syrian Desert. En route, the Armenians were subjected to brigandry by militias of Ottoman citizens. As with other genocides, the active participation of the majority population was enabled by years of conditioning wider Ottoman society that the Armenians were a “problem” that needed to be “dealt with”. The museum featured exhibits with stories and photographs of entire families slaughtered, with no, or only single survivors. There were towns where over 90% of the Armenian population were murdered. It is estimated that over 1 million Armenians died during the genocide.

Sexual violence and kidnapping were also a part of the genocide. Armenian women were raped during the deportations, and forced to convert to Islam and marry Ottoman men. Children were taken from Armenian parents and put in orphanages to detach them from their Armenian cultural heritage. The purpose of this was to destroy the Armenians are a separate cultural and ethnic identity, which by kidnapping women and children, as forcibly assimilating them into the Turkic culture, the Ottoman authorities hoped to achieve.

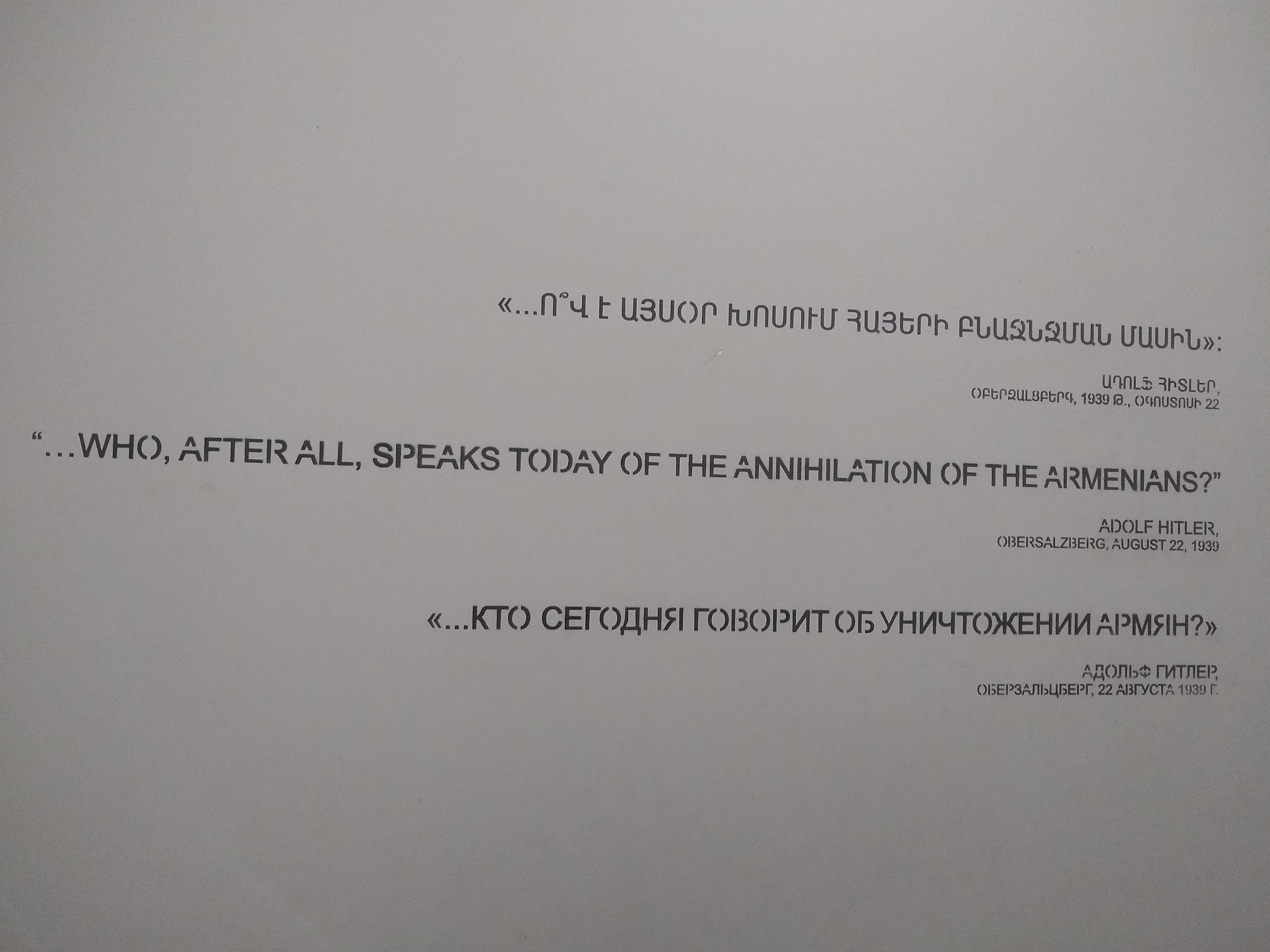

After the conclusion of the First World War, there was an attempt to punish the perpetrators of the genocide. However this was disorganized, and with the final collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of the Republic of Turkey, many of the key figures implicated in the Armenian genocide were never punished. One of these was Talat Pasha, who lived freely in Germany, until he was assassinated by Soghomon Tehlirian acting for the Armenian Revolutionary Federation during Operation Nemesis, an Armenian operation to assassinate key Ottoman figures involved in the genocide. He was found not guilty after presenting a case that featured testimony from witnesses of the genocide. In time, the Armenian genocide became an overlooked detail of the First World War, prompting the quote attributed to Hitler (Figure 5) on the eve of the Nazi invasion of Poland. Nevertheless the events of the Holocaust reignited interest in the genocide, and the two events prompted the lawyer Rafael Lemkin to coin the term “genocide” to describe the events of both the Armenian genocide and the Holocaust.

The final phase of genocide is denial. To this day, Turkey denies that the events constituted genocide.