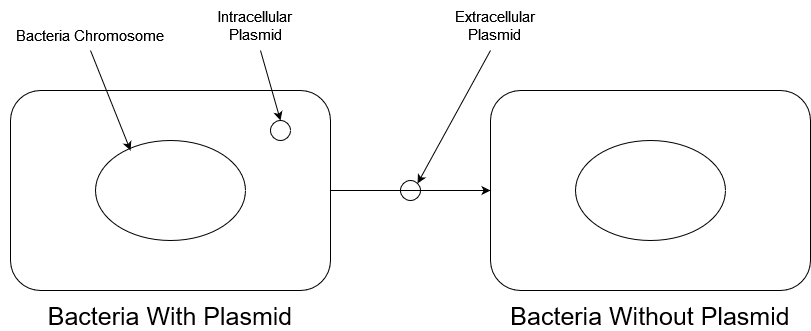

Bacteria are prokaryotic organisms which do not have their genomes organized into chromosomes like animals, plants, fungi and other eukaryotic organisms do. Instead, bacteria have a single circular DNA sequence as a single chromosome and may additionally have small circular sequences of DNA known as plasmids (Figure 1).

Bacteria do not reproduce sexually. Rather, provided they have the resources to grow, they divide into daughter cells with the same genetic content as the parents. This means that their genomes do not get mixed with the genomes of other individuals in their species in the way that eukaryotic organisms do, and so there is less chance to combine desirable traits in offspring when those traits are found in separate individuals. To offset this disadvantage, bacteria can use plasmids, which provide a way that bacteria can carry out something comparable to sexual reproduction.

Plasmids are short circular sequences of DNA that can be transferred between bacteria in order to exchange genetic material between them. Bacteria will commonly uptake plasmids when they are under stress, so plasmids are often used to share genes that improve bacterial survival, such as antibiotic resistance.

As plasmids can be used to introduce genes into bacteria, and they are easy to isolate and manipulate, they have widespread use in scientific research and biotechnology. Plasmids can be manipulated using molecular biology techniques to insert and remove sections of DNA, and thus create bespoke plasmids that have different applications. Plasmids can be introduced to bacteria by exposing the bacteria to stress. The two main ways of doing this at to use heat or to use electricity. In research and biotechnology applications, bacteria must be prepared in advance to allow them to uptake plasmids like this, but in the environment, natural stresses encourage the bacteria to take up plasmids when needed in the same way.